| The images and descriptions below of canvas art paintings by masters were provided by Jock Stewart from Sydney. These masterpieces provide an insight into the the symbolism and significance of foods in work of art.

I recently reviewed a DVD, Eating Art by Oliver Peyton, where he uncovers the history and stories behind the paintings of food on canvas. This got me thinking that there many famous paintings of cooks and food that I was familiar with and that I should know about, so I decided to look more carefully into this and have decided that I would share some of my favourite paintings with others.

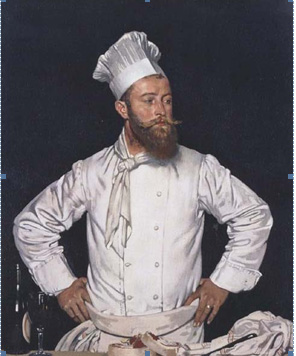

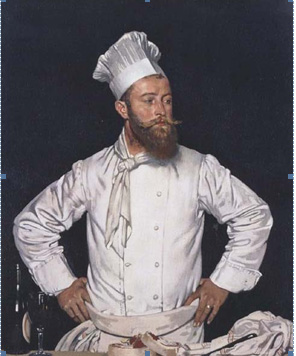

Le Chef de le Hotel by Sir William Orpen.

.

This painting by Irish portrait artist, Sir William Orpen, Le Chef de le Hotel is of a Parisian chef in 1921 and the portrait conveys vividly the professional pride, authority and self-assurance that marked cooks who had been trained by Escoffier in the First World War or who had worked in kitchens he had organized or influenced. This portrait epitomises the authority of the chefs that I did my training under.

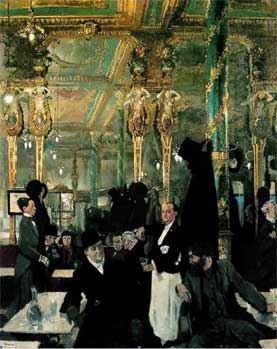

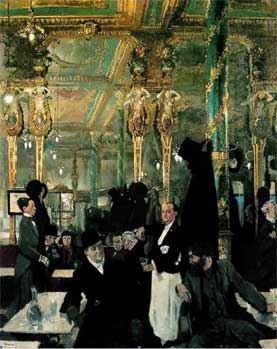

The Cafe Royal by Sir William Orpen

As usual the artist Sir William Orpen includes himself in the painting. He is seated at left, wearing a bowler hat.

‘In the Kitchen’, by G. Marchetti from ‘L’Illustration’, December 1893.

In this painting we see inside a busy Parisian restaurant kitchen on Christmas Eve, with the sweat pouring off the chefs, the lobster is on a platter ready for service and in the middle is a chef putting the final preparations to another dish. The heavy copper pots and pans hanging from a rack. Work like this meant periods of exhausting activity for cooks working in the big kitchens. You can see the tension, here, but at the end of the shift the brigade often took a triumphant pride in the work that they had achieved. You will also notice that the chefs have their knives in sheaths around their waists. This is a painting that we should thank our lucky stars that we no longer have to work in conditions such as this. Nowadays our kitchens are air-conditioned.

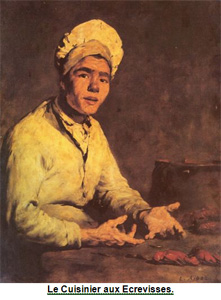

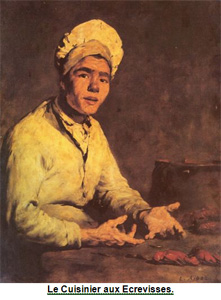

Kitchen Scene.

I have always loved the way that French artist Theodule Ribot portrayed people in the kitchen. In 1861, he exhibited four paintings at the Paris Salon, where he used the kitchen theme to present the cook as a hero of modern life. Ribot soon became fully identified with this type of image; during his career he returned to the cook in a variety of activities. This led the profession of cook to acquire a new significance and visibility. Ribot, was probably the only artist of the time to take an interest in the life of a working cook. Cooks were visualized preparing meals, working in the kitchen and even drinking.

The cooks.

Here we see cooks plucking birds. I wonder how many of our young chefs and apprentices have done this

To me this is a great painting, because it shows a chef at work oblivious of all that is going on around him. You can see the concentration on his face. I would guess that this is probably a chef in wealthy house.

The Cook Accountant.

Here we see the cook-accountant keeping the record books of his establishment. This was obviously before calculators or computers were invented.

The objects on the floor (in this canvas), as much as the food and ink-well on the small table, demonstrate that Ribot was a major force in the still-life revival in France.

In this small painting, a butcher boy tempts a cat with a slice of meat.

The cook and the cat.

In this painting, a cook is trying to work something out whilst the cat tries to steal a fish from the floor.

Here the subject is the young cook helping himself to a bottle, unaware he is being observed, this was intended to amuse.

The next couple of paintings show the sordid side of our profession.

This is a digital manipulation by Elikozone of Ribot’s, The Cook & the Cats.

Everyone knows what a magnificent and amazing musician and composer Beethoven was and how he changed the world with his music. But I wonder how many people know that at one point in his career he aspired to become a cook. There is a story told by his former student and long time friend, Ferdinand Ries, in the book, Beethoven Remembered… Apparently Beethovens difficult personality was not just in social situations, but reached down to touch his most intimate connections. He was forever hiring and then firing household help. He was extremely hard to please and took offence at the smallest infractions.

So one day after firing yet another cook, he decided that he could do just as well if not better, and set about reading piles of cookery books and teaching himself to cook.

Beethoven, was a very intense person , who was totally focused on whatever he was doing at that time, and so in typical Beethoven fashion he completely immersed himself in his new passion, so much so that in a few short months he completely abandoned his composing, He could often be seen coming home from the markets with a wide variety of vegetables and meats, where he would retire to his rooms for hours on end and produce some marvelous dishes, and he gained enough confidence in his abilities to plan a dinner party for his friends, unfortunately because of his lack of timing dinner would often be served hours late.

Eventually when everyone sat down to the meal and Beethoven began to serve the dinner, the meal turned out to be interesting . Several dishes were unrecognizable, and the ones that the guests could recognise were inedible. They all proceeded to push their food about on their plates in feigned enjoyment , whilst winking at each other in veiled amusement. Beethoven, on the other hand ate heartily and proclaimed that each course was better than the previous.

At the end of the night Beethoven declared that the evening was a great success and from that point on he went back to composing and he never did any more cooking because he felt that he had conquered the kitchen and all that there was to it.

Beethoven, may have been a great man and was well-loved and highly respected by many but I don’t think that he could ever have understood what it means to be cook. A bit like the people who appear on these cooking reality programs.

Cook in front of the Stove by Pieter Aertsen.

The cook is firmly positioned in front of the imposing chimney-piece, the cook stands surrounded by the food she is preparing to cook: voluminous cabbages in a basket, and fowls and a leg of meat skewered on a spit which she holds firmly in one hand, whilst with the other she grabs a skimming ladle. The sculptural silhouette with its powerful arms, its solid body and vigorously modeled face radiates a strong sense of assurance. The fact that she is looking towards the unseen part of the room suggests that something is going on there that the viewer is unable to see.

The Kitchen Maid by Pieter Cornelisz van Rijck.

The painting shows a central female figure in a larder surrounded by still-life elements. She poses with her hand on a cabbage – a common erotic allusion in paintings of this kind.

The Kitchen Scene by Pieter Cornelisz van Rijck.

It is a naughty picture in 16th century terms – all the meat is clearly a metaphor for the pleasures of the flesh, the old woman looks like a matchmaker (or worse, a procuress), and the young cook in the centre is clearly in some disarray, with her partlet undone. The picture is of course a very moral one.

The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer.

When you look at this painting you will see the quiet concentration of a woman pouring milk into a bowl. With her left hand she supports the jug she is pouring from. Around her are various objects: a loaf of bread, a stoneware bowl which is made of clay that produces a grey or brown colour and is fired at a temperature of around 1250 degrees Celsius. It is exceptionally hard and only slightly porous. Moreover, stoneware does not acquire a taste and is easy to clean. It is therefore an ideal material in which to preserve liquids and from which to drink, a jug, a basket and a brass bucket. The woman is standing near the window so she can see what she is doing. The light falls on her hands; her silhouette is dark against the white wall. Although the artist observes his model from nearby, she continues with her work, totally unperturbed.

Clearly, this woman is a servant and no grand lady. Her dress is simple. Her blue skirt is tucked up to save it from getting dirty. She wears green over-sleeves which partly protect her yellow bodice. On her head the maid wears a starched cap. She looks strong and sturdy, clearly a woman at her work.

Cupid appears in the painting on the tile (lower bottom right) between the maids skirt and the foot warmer, preparing to shoot his bow. This is obviously a Deft floor tile.

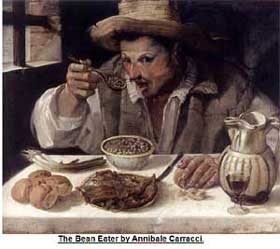

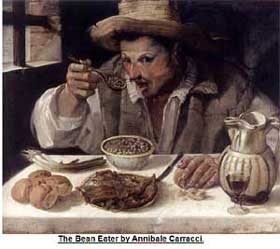

The Bean Eater by Annibale Carracci.

I find this painting by the Italian artist Annibale Carracci very interesting because it is hard to tell exactly what the artist is trying to convey with his subject. Here we have a peasant having his lunch, the man eats and drinks well, but the setting is evidently meant to be rough. Look at the crumbling plaster on the brickwork of the window. Look at the splitting brim of his straw hat, his bared chest.

Maybe his diet of beans has behind it a timeless fart joke. Certainly the way he’s caught in the very act of eating has some gross humour. And to be shown open-mouthed, and as a visibly messy eater his spoon stops between bowl and mouth, and a slurp of juice drops from it to go a notch further.

He catches our eye. What seems to have interrupted him, mid-mouthful, is the presence of the viewer. It’s an unusually intimate bit of staging, as the table is brought right up to the front of the picture. It’s as if you were seated directly opposite the eater, almost sharing his meal with this fellow.

Slaughtered Ox by Rembrandt.

Rembrandt painted a small picture of a slaughtered ox. A big chunk of meat hanging from a wooden construction in a dark room. The ox is beheaded and skinned, organs and hooves removed from the body. The carcass is lighted from a light source invisible for the viewer. The background is dark, but still recognisable is a wall with a door and what looks like a small window. In the door stands a white capped woman, just peeking around the corner. It is hard to say if she is looking at the carcass or directly at the viewer.

When Rembrandt painted the picture, he probably would not have realised that the painting would still spark debate in the twenty-first century. The gloomy atmosphere and the absence of other elements than a large carcass, a dark room and a woman in the background make it a mysterious work. Why did Rembrandt paint a carcass? Is there a meaning behind the work? Or is it just a dead ox?

An important question to ask when examining the painting is where the subject originates from. When the image is traced back into time, one quickly comes across the parable of the prodigal son. This biblical story tells about a son who leaves his father. The son spends all his money and after realizing he has gained nothing and lost everything, returns again to his elderly home. There his father greets him with open arms and orders the slaughter of the fatted calf to celebrate his homecoming, and this can be seen in this painting.

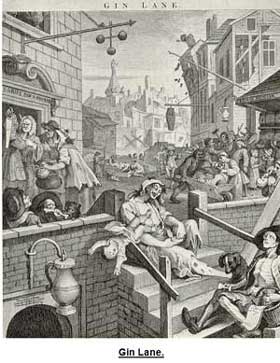

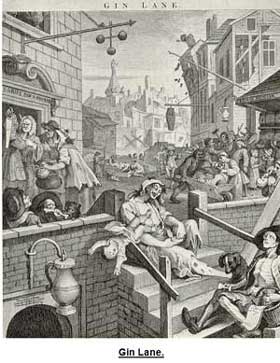

There is much to see in these two magnificent prints: Beer Street and Gin Lane by English artist William Hogarth.

They are designed to be viewed alongside each other. They depict the evils of the consumption of gin as a contrast to the merits of drinking beer. On the simplest level, the artist portrays the inhabitants of Beer Street as happy and healthy, nourished by the native English ale, and those who live in Gin Lane as destroyed by their addiction to the foreign spirit of gin; but, as with so many of Hogarth’s works, closer inspection uncovers other targets of his satire, and reveals that the poverty of Gin Lane and the prosperity of Beer Street are more intimately connected than they at first appear. Gin Lane shows shocking scenes of infanticide, starvation, madness, decay and suicide, while Beer Street depicts industry, health, bonhomie and thriving commerce

Gin drinking was so serious a problem in Hogarth’s time that an act of parliament was passed in 1751 to curb its production. People were selling anything that they could in order to buy gin. The only businesses that flourish are those which serve the gin industry: gin sellers; distillers the pawnbroker where he greedily takes the vital possessions (the carpenter offers his saw and the housewife her cooking utensils). Most shockingly, the focus of the picture is a woman in the foreground, who, addled by gin and driven to prostitution by her habit as evidenced by the syphilitic sores on her legs lets her baby slip unheeded from her arms and plunge to its death in the stairwell of the gin cellar below, noted by the sign outside the cellar. Half-naked, she has no concern for anything other than a pinch of snuff. Other images of despair and madness fill the scene: a lunatic cavorts in the street beating himself over the head with a pair of bellows while holding a baby impaled on a spike the dead child’s frantic mother rushes from the house screaming in horror, below the woman who has let her baby fall, An ex-soldier, he has pawned most of his clothes to buy the gin which shares space in his basket with the pamphlet which denounces it. Next to him sits a black dog, a symbol of despair and depression. Images of children on the path to destruction also litter the scene: aside from the dead baby on the spike and the child falling to its death, a baby is quieted by its mother with a cup of gin, and in the background of the scene an orphaned infant bawls naked on the floor as the body of its mother is loaded into a coffin on orders of the beadle. Two young girls who are wards of the parish of St Giles indicated by the badge on the arm of one of the girls’ each take a glass.

In comparison to the sickly hopeless residents of Gin Lane, the happy people of Beer Street sparkle with robust health and bonhomie. “Here is all is joyous and thriving. Industry and jollity go hand in hand”. This picture celebrates the virtues of the mildly intoxicating traditional national drink. Beer inspires artists and refreshes tradesmen and labourers. It can be drunk safely on rooftops. The newfangled foreign spirit gin, however, inspires violence and careless inebriation. Addiction to spirits leads to negligence, poverty and death.

The only business that is in trouble is the pawnbroker, who lives in the one poorly-maintained, crumbling building in the picture. In contrast his Gin Lane counterpart, who displays expensive-looking cups in his upper window (a sign of his flourishing business). In this picture the pawnbroker displays only a wooden contraption, perhaps a mousetrap, in his upper window, while he is forced to take his beer through a window in the door, which suggests his business is so unprofitable as to put the man in fear of being seized for debt. The sign-painter is also shown in rags, but his role in the image is unclear.

The rest of the scene is populated with doughty and good-humoured English workers. Under the sign of the “Barley Mow”, a blacksmith or cooper sits with a foaming tankard in one hand and a leg of ham in the other. Together with a butcher-his steel hangs at his side-they laugh with the coach-driver as he distracts a housemaid from her errand. Close by a pair of fish-sellers rest with a pint and a porter sets down his load to refresh himself. In the background, two men carrying a sedan chair pause for drink, while the passenger remains wedged inside, her large hoop skirt pinning her in place. The inhabitants of both Beer Street and Gin Lane are drinking rather than working, but in Beer Street the workers are resting after their labours all those depicted are in their place of work or have their wares or the tools of their trade about them-while in Gin Lane the people drink instead of working. The picture serves as a counterpoint to the more powerful Gin Lane Hogarth intended Beer Street to be viewed first to make Gin Lane more shocking but it is also a celebration of Englishness and depicts of the benefits of being nourished by the native beer. No foreign influences pollute what is a fiercely nationalistic image.

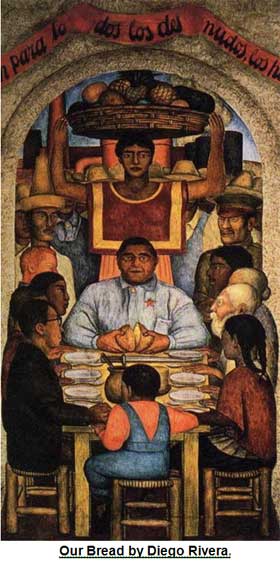

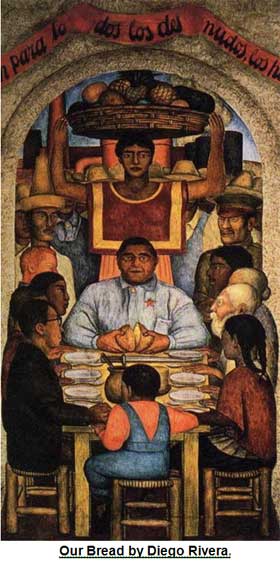

Our Bread by Diego Rivera.

I find this painting by Mexican artist, Diego Rivera interesting because the artist shows Communism, in the form of the provider at the head of the table about to say Grace for the supply of food, as representatives of the Mexican nation look on inreverential gratitude.

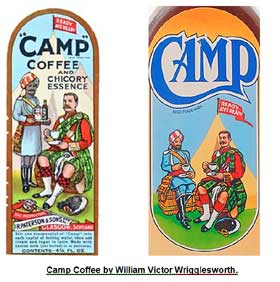

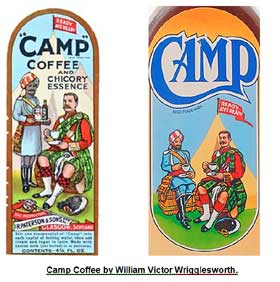

No self respecting Scotsman would leave the following paintings out of this collection of paintings about food.

Camp Coffee by William Victor Wrigglesworth.

All Scottish chefs will be familiar with the painting on the bottles of Camp Coffee.

The original label consisted of a drawing of a Gordon Highlander soldier (allegedly Major General Sir Hector Macdonald) and a Sikh soldier carrying a tray of coffee outside a tent, from which flies a flag carrying the drink’s slogan, “Ready Aye Ready”. This slogan uses the form of the Scots “aye” meaning yes so the drink was “Ready Always Ready” to be made. The original drawing was by William Victor Wrigglesworth.

The makers of Camp Coffee have changed the label on their famous jars – after complaints of racism, they are now using an image of a Scottish soldier sitting side by side drinking coffee with a turbaned Sikh.

The Central Scotland Racial Equality Council has welcomed the latest updating claiming that it will help change the mentality of young people to see how different races now relate.

Mukami McCrum, director of the council added: “It is an encouraging and progressive move. Times have changed and it is heartening to see that a new message is being sent out.”

For those who don’t know what Camp Coffee is it is a Scottish food product, which began production in 1876 by Paterson & Sons Ltd. in a plant on Charlotte St, Glasgow, where it is reported to have been the worlds first instant coffee. Camp Coffee is a glutinous brown substance which consists of water, sugar, 4% coffee essence, and 26% chicory essence. This is generally used as a substitute for coffee and is said to have originated when the Gordon Highlanders requested a coffee drink which could be brewed up easily by the army on field campaigns in India.

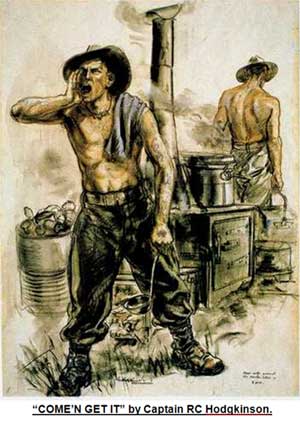

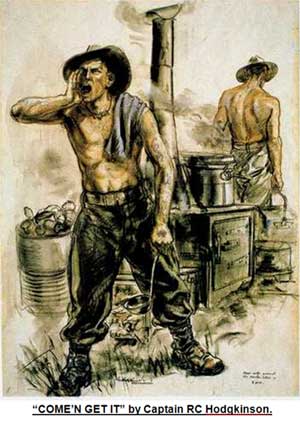

COME N GET IT by Captain RC Hodgkinson.

This painting is familiar to all Australian Army Catering Corps cooks, it was painted by the war artist, Captain Hodgkinson who visited the diggers at Finschhafen during the Huon Peninsula Campaign in New Guinea between September 1943-April 1944, At first Captain Hodgkinson did a crayon sketch of a cook, which is now held by the Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

The cook is standing in front of Fowler stoves which were standard mobile kitchen equipment. The cook is seen shouting, �Come and it or I ‘ll chuck it out!

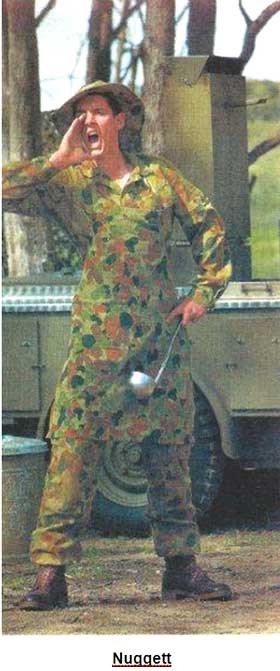

Nuggett.

The soldier who was the modern face of Nuggett was Private James Lear Australian Army Catering Corps..

Jim was chosen to represent the new face of Nuggett while he was completing

his Initial Employment Training (IET) as an Army Cook. On completion of his

IET Jim was posted to 1 BASB (1st Brigade Administrative Services Battalion

– now Combat Service Support Battalion), and arrived in Darwin late 1995 /

early 1996. At that time most of the 1st Brigade units were still located in

Sydney and were just commencing the move north, as Caterer 2nd Cavalry

Regiment Graeme Alexander became the de facto Brigade Caterer and managed the other unit Catering advance parties, feeding the Brigade’s soldiers then located in Darwin from Waler Lines (now Robertson Barracks). Unfortunately Jim had an

accident suffering damage to his knee and was subsequently medically

discharged late in 1996.

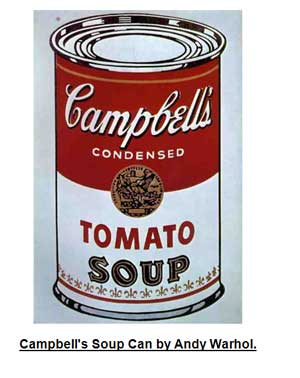

No collection of food paintings would be complete without one by pop artist Andy Warhol. It was during the 1960s that Warhol began to make paintings of iconic American products such as Campbell’s Soup Cans.

Campbell’s Soup Can by Andy Warhol.

|